Tariffs and Inflation: Will Trump's Trade Policy Backfire

“To me, tariff is the most beautiful word in the dictionary”, Trump reiterates as he imposes additional tariffs on Canada and Mexico, and threatens to put more tariffs on the EU. Tariffs, taxes on imported goods, "will just make everything more expensive” Senate Finance Committee member Ron Wyden says. So why does Trump like them so much? Besides claiming it will help in his quest to stop illegal migration and drug trade, he insists it will make America ‘rich again’. Trump argues tariffs will spur American industry, and gain the country lots of revenue which he will use to ‘fix’ the budget deficit and decrease taxes to grow the economy- “We are going to boom like we’ve never boomed before.”

However, not everyone is convinced. Consumer’s inflation expectations are at the highest level since 2022 due to concerns surrounding Trump’s tariffs. Jerome Powell, chair of the federal reserve, argues tariffs will raise consumer prices. Furthermore, Many economists claim the ‘tariff plan’ won’t work out the way the president thinks it will.

Nevertheless, while critics believe it will lead to the dumbest trade war in history, Trump's opinion remains unchanged. Will tariffs deliver the promised economic benefits, or will they backfire and spike inflation?

Make America a manufacturing superpower again!

Trump argues tariffs will grow domestic industry, specifically manufacturing. We’ll make America a manufacturing superpower again (…) the golden age has begun” Trump said at the World Economic Forum on January 24. Since 2016, Trump has been promising to bring back manufacturing to the United States. This mainly in response to the China-shock which displaced millions of manufacturing workers by providing cheap alternatives to American made products. “We’re taking back things that have been taken from us many years ago “.

So how exactly will tariffs grow domestic industry? Trump’s argument is based on two economic premises: relocation of firms into the United States and directly growing the domestic manufacturing industry. The former is quite simple. Firms, as Trump puts it, have two choices; produce domestically or face tariffs. Reuters reports that this choice is already yielding results, as several large companies are eyeing relocation to the US to avoid tariffs.

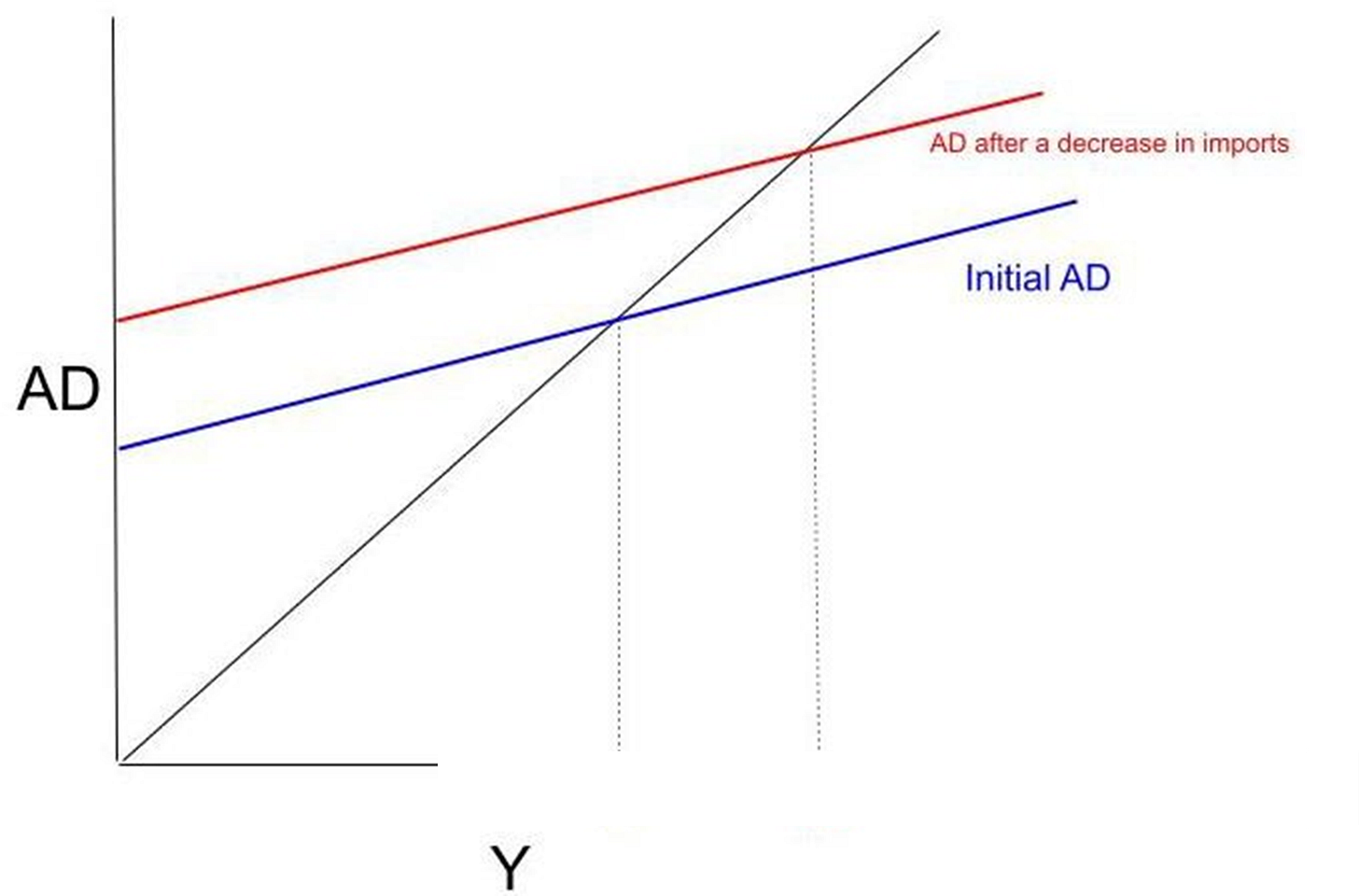

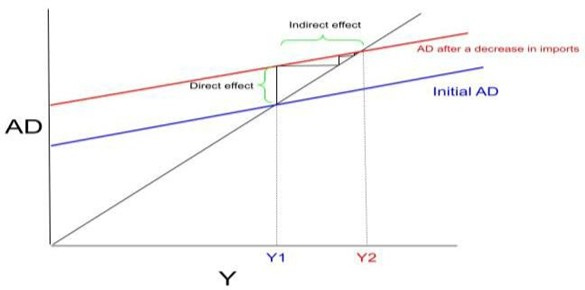

Now, the second premise is more complicated. Let us look at a simple multiplier model. We plot aggregate demand (AD) on the vertical axis, and output (Y) on the horizontal axis. We assume that supply equals demand such that Y = AD (the 45-degree line shows all values for which this equation is satisfied). Intuitively this makes sense, since the entire income (Y) of an economy also gets spent again (AD), making it a repeating cycle.

1) 𝐴𝐷 = 𝑐0 + 𝑐1(1 − 𝑡)𝑌 + 𝐼 + 𝐺 + 𝑋 − 𝑚𝑌

Aggregate demand is composed of some autonomous consumption (view this as consumption which does not depend on total income). Further, people consume a fraction 𝑐1 of total disposable income (1 − 𝑡)𝑌. Income which is not consumed is invested (I), and the government spends the revenue from taxes (G). Most importantly for us, net exports (X - mY). An economy exports goods (X) and it imports goods (mY). The difference is called the balance of trade.

All else equal, a decrease in imports will increase domestic demand, which will increase output (y1 -> y2). This is represented in figure 2. The blue line is the initial situation, the red line represents the situation when imports decrease.

So why do imports decrease? Imagine a situation where either a producer or consumer must choose between a combination of domestically and foreign produced goods (imports).

Intuitively, we can already imagine that an economically efficient agent will choose to buy more domestic goods if they become cheaper relative to foreign produced goods. Thus, the direct effect of imposing tariffs would be an increase in demand for domestic goods. The indirect effect is the long-run increase in investment (=growth) into domestic industries due to the initial increase in demand.

Take Biden's EV tariffs which increased domestic EVproduction as a recent example of how this process works. Trump’s plan seems to be working as Apple, Nvidia and other firms invest trillions in response to increased demand expectations.

However, many economists agree Trump is ‘wrong on tariffs’. A primary concern is that for tariffs to work, the elasticity of demand for imported goods has to be high enough. So, are people sufficiently able to substitute domestic for imported goods? Data shows that the US does not possess the immediate manufacturing capabilities to meet increased demand.

Additionally, economists say America does not even have enough workers to increase production.

“Revenue that will make America rich”: Fixing the budget deficit and cutting taxes

Another one of Trump’s major arguments for tariffs is the idea for additional revenue that he hopes to generate. This would make hefty tariffs on imports the go-to solution, à la Trump, to balance the federal budget , which is part of his broader plan to increase government efficiency. Amid headwinds, even from within his own party, he has also stated that the revenue generated by these tariffs could allow for tax cuts, which in turn could further stimulate the economy. Trump doesn’t shy away from making bold claims. And, in typical Trump fashion, this one is wrapped in oversimplification, but also in a kernel of economic logic that deserves some attention.

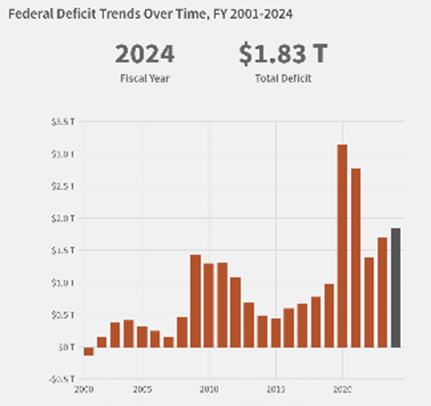

Starting off with the basics. The federal budget is essentially a big spreadsheet that tracks how much money the U.S. government brings in and how much it spends. When the government spends more than it earns in revenue in a given period (usually a fiscal year) it is referred to as a budget deficit. When that happens (as it has every year since 2001), the Treasury covers the shortfall by borrowing money, which in turn adds to the national debt. To do so, it borrows by issuing government bonds, which are bought by the Federal Reserve and private investors, both domestically and abroad.

These borrowing practices often raise concerns, but running a deficit, despite its egative connotation, isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Actually, economists claim deficits are often necessary during economic downturns or emergencies, like in the 2008 financial crisis and 2020 Covid-19 pandemic. As economist Gus Faucher puts it; “... budget deficit is probably a good thing because that means the government is spending money to stimulate the economy”. Furthermore, as long as GDP growth outpaces the interest owed on that debt, deficits remain manageable.

The issue, however, is that those deficits didn’t just disappear when the crises passed; they stuck around, quietly stacking up even in the so-called ‘good’ years. And now with interest payments ballooning, the budget picture is starting to look a little daunting, even for economists, who usually don't get spooked by red ink.

Trump’s solution? Tariffs. Lots of them. His argument is that tariffs will generate ‘revenue that will make America rich (and great!) again’, through an external revenue service or, to quote Trump directly: “We’re going to raise hundreds of billions in tariffs; we’re going to become so rich we’re not going to know where to spend that money”. The idea is simple: if the U.S. imports $3 trillion worth of goods, and you slap a 25% universal tariff on, you bring in $750 billion per year in new revenue. That’s a serious new cash inflow! Trump says this money can be used to reduce the budget deficit, pay down the national debt.

Trump also argues tariffs will enable tax cuts which could stimulate the economy. How? Since people will have larger disposable incomes, consumption will increase which will lead to more profits for firms. This will lead to more investment -> more income -> more consumption etc... (=economic growth). Let’s look at the multiplier model again. We see that a decrease in t will increase C₁(1−t)y and, in turn, increase output (Y).

However, tariffs alone won’t plug the budget hole. In 2024, the US spent 6.9 trillion dollars, while in the same year, revenue derived from tariffs only amounted to $77 billion. Even if that number jumped to a few hundred billion (from the new tariff policy), it still wouldn’t come close. Therefore, tariff revenue barely makes a dent, something Trump rarely emphasizes in his pitch.

Moreover, Trump’s two main arguments, that we addressed, appear to contradict each other. If his plan to grow domestic industry succeeds, the volume of imports, and thus the tariff base, will shrink. This works against his second argument, that tariffs could generate enough revenue to reduce the deficit and fund tax cuts. In short, the more effective the first argument becomes, the less feasible the second one gets.

Inflation Dilemma: Will inflation rise?

Finally, Trump's tariff policies aim to create manufacturing jobs and boost the US economy, but tariffs work as a double-edged sword since some economists believe it will raise inflation.

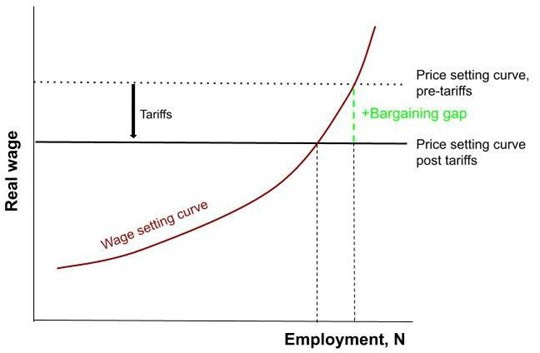

Inflation is defined as a sustained rise in the general price level. Jerome Powell, chair of the fed, argues tariffs will cause inflation. Even Trump ‘says’ he can't guarantee that they won't. To understand this, we turn to the Philips curve, which demonstrates the trade-off between unemployment and inflation. Tariffs raise the production and material costs for manufacturers who pass them down to consumers (cost-push inflation). This erodes workers’ real wage, shifting down the price setting curve. This creates a bargaining gap, leading workers to demand higher wages (figure 4). Firms then raise prices to offset the higher labour costs, causing inflation. On top of this, workers demand expected inflation (last year’s inflation) to be incorporated as well, which economists argue is high due to increasing inflation worries. In this scenario, inflation is equal to the bargaining gap + an amplified expected inflation.

The economic implication of tariffs also depends on their duration. Persistent tariffs exacerbate the risk of wage-price spirals. Prolonged tariffs will cause the bargaining gap to remain. This will shift the Philips curve upwards, since inflation = the bargaining gap + last year’s inflation. The same employment level will have increasingly higher inflation, if tariffs persist. Hence, Economist Marcus Noland highlights how tariff-made trade war tensions can cause reciprocal tariffs and cause increasing inflation. This is why economists fear escalating trade wars i.e. tariffs in response to tariffs. China and Canada have already responded to the US's taxes by retaliating with their own. Tariffs are known for their counter productiveness, and potential to trigger further retaliation and inflation through increasingly higher tariffs which will persistently cause higher costs.

Trade wars will complicate things for the fed. In an attempt to control inflation by raising interest rates, they risk slowing the economy. Yet, the Trump administration argues a potential recession would be a price worth paying. The reason? You guessed it. Growing American industry and raising revenue.

Nevertheless, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent believes the tariff inflation effects will be limited, and S&P Global anticipate a one-off price increase only. Scott Bessent argues that tariffs will not lead to a persistent bargaining gap. For example, steel tariffs during Trumps first term in 2016 had a minimal effect on the consumer price index (CPI). Prices didn't rise until 2021 when pent-up demand increased consumption post-pandemic. This suggests that while tariffs can induce cost increases in specific sectors, their broader inflationary impact depends on how businesses and consumers adjust. If companies can adjust supply chains following an increase in prices, inflation may be limited. Furthermore, the strength of tariffs also matters. Brown University states tariffs of 10% don't significantly affect the overall economy. However, Trump's 2025 policies advocate for tariffs of up to 25%, a rate that is more than double that threshold.

In conclusion, the economic impact of Trump’s policies remains uncertain. While the White House argues in favour of the policies, others raise concerns about potential backfiring by increasing inflation and economic instability. Whether the tariffs will deliver their promised economic benefits, only time will tell.